Skin grafts for burns injuries can lead to crippling scars – a drug that blocks the skin’s ability to respond to physical stimuli could promote healing, new research in pigs finds

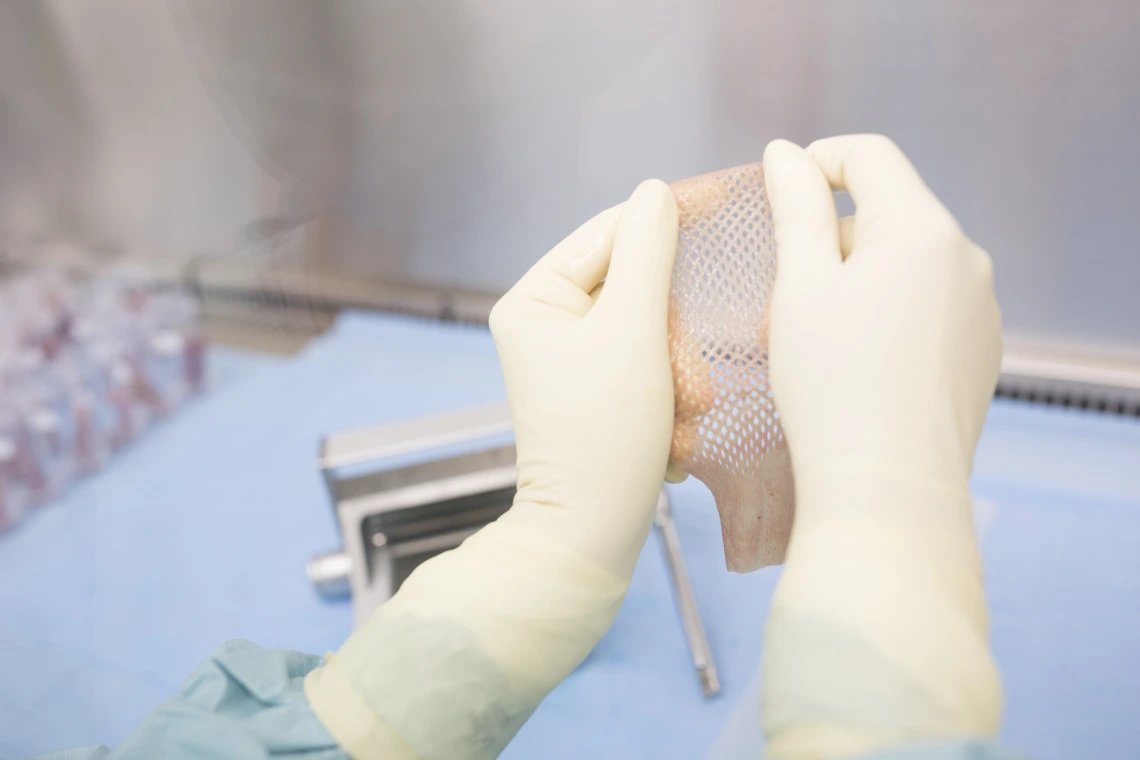

Skin grafts are often meshed to maximize the surface area they can cover.

Westend61/Getty Images

The big idea

Reducing a skin graft’s responsiveness to its physical environment could help improve healing and reduce scarring from large injuries like burns or blast wounds, according to our recent study published in Science Translational Medicine.

Historically, injuries that cover massive areas of the body like burns have high death rates. Over the past 50 years, advances in wound care using techniques like skin grafting have often allowed patients to survive. During this process, a thin layer of healthy skin is removed from an undamaged area of the body and transplanted to cover the burn. Typically, these skin grafts are meshed, or perforated, in order to cover larger areas, much the way a chain-link fence covers more space overall than a solid metal wall of the same weight.

Skin grafts are often meshed to maximize the surface area they can cover.

Westend61/Getty Images

However, skin grafting still leads to long-term problems. Grafts can contract, shrinking in size and becoming much more dense and filled with scar tissue. If these skin contractions occur over joints or the face, they can restrict movement and become crippling over time. The appearance of the scar tissue may also be unappealing to patients. The only treatment currently available for skin contractions is to remove the affected graft and replace it with a new one. But because skin contractions can re-form, this can lead to a vicious cycle, with some patients receiving more than 60 repeat operations over the course of their lives.

Read the full story in The Conversation.